Association of Washington School Principals

Volume 2 – 2020-21

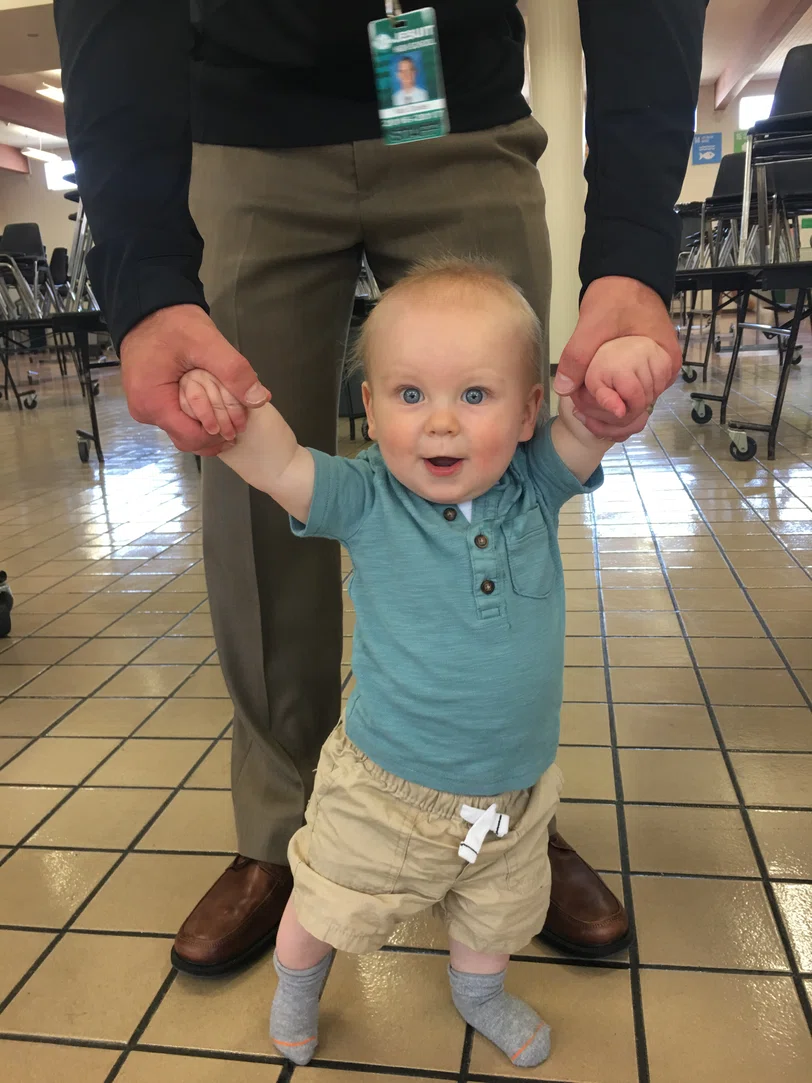

What my toddlers

have taught me

about high school

Failure IS — and should be — an option

Evaluation Criteria: Creating a Culture; Improving Instruction; Engaging Families and Communities; Closing the Gap

Nick Davies

Associate Principal/Athletic Director, Vancouver PS

I want to start with a little bit about me to give some context to this short article.

I know that this will not be groundbreaking information to anyone, but it should hit home. I am an associate principal and athletic director in Vancouver. Our district has been working with Dr. Yemi Stembridge and his book, “Culturally Responsive Education,” which focuses heavily on equity. I am in the process of earning my Ph.D. in education, and my focus will be on curriculum implementation. I also recently re-read the short essay, “All I Really Need to Know I Learned in Kindergarten,” by Robert Fulghum. Finally, I am the father of two energetic boys, and they have five cousins who live nearby. All of the children in my family are under eight years old.

During this global pandemic, I have reflected a lot on what is going on in our schools. The things mentioned in my background have led me to think about the kids in my family and what they can teach us about our high schools.

Some kids walk before they are a year old, and others take until they are pushing a year and a half. What is the same among these kids with differing abilities? Their parents are relentless in encouraging their kids and giving them opportunity after opportunity to walk.

Let’s start with equity. Parents do not treat their children the same. We spend enormous amounts of time getting to know these kiddos. That is how I know to keep the dog away from my older son when he is playing on the floor because he hates getting licked in the face. At the same time, my younger son likes it when the dog does that. How we discipline each kid is different depending on age, circumstance, and history. There is no one-size-fits-all approach. Equality does not work with parenting, and it does not work in the classroom.

I hear from teachers, “But it’s not fair if I do this for one student and not another.”

This is where assigning zeros comes in. Being a former math teacher, I know how common it is to post a zero for a late assignment. These zero policies are the norm in many classrooms. The argument goes, “We need to teach these students accountability. How will they learn to hold themselves accountable if we do not hold them to deadlines? They need to learn to persevere and keep fighting when their grade gets low.”

Ignoring the math behind how detrimental a zero is, that perspective shows a hidden curriculum that not everyone realizes is present in schools.

Back to the kids in my family. When they were learning to walk, we did not practice for a bit, set an arbitrary deadline, and tell the kids, “You missed the deadline, too bad!” Some kids walk before they are a year old, and others take until they are pushing a year and a half. What is the same among these kids with differing abilities? Their parents are relentless in encouraging their kids and giving them opportunity after opportunity to walk.

Learning to walk and run can be physically painful too, but that doesn’t stop the kid. My son recently tripped while holding a bowl, and he could not break his fall. It resulted in a nicely chipped front tooth. He “failed” at walking at that moment, but he got back up and continues to walk and run and jump and fall. We do not even need to get into the number of times our kids “fail” at eating or potty training.

How about this for accountability and perseverance: You fail, you do it again. If you fail a second time, do it again. And again. And again. Accept nothing less than meeting the standard.

Our kids don’t know anything but encouragement and the belief that they will succeed. Their parents, family, and family friends all believe they will grow, and what happens? They succeed, because the people around them never give up. I firmly believe that every student that walks into our school can succeed as well. But what message of despair are we sending them? We want our students to learn to be accountable and to persevere through adversity. But then we do that by assigning zeros or not allowing them to make up failed tests. The hidden curriculum is that we are teaching them to give up. We are teaching them that failure is final. There is no opportunity to make up the work, so how can they honestly be held accountable for their failure?

How about this for accountability and perseverance: You fail, you do it again. If you fail a second time, do it again. And again. And again. Accept nothing less than meeting the standard. Once students meet the standard, give them full credit for it. Walking is walking. Achieving the standard is achieving the standard. We can do this by believing that all students, no matter what, can succeed. We can do this by getting to know our students and giving them the support they need. We can do this by treating our students as our children.

Adults accept that little kids will fail. They accept that all little kids are different and need different things. These are natural parts of life and little kids succeed with encouragement and an unlimited number of opportunities to “meet the standard.” Why, then, have we decided that these students, without fully developed brains, should be treated any differently at the high school level?

My children have taught me valuable lessons about equity and the power of zero. In the infamous words of Samuel Beckett, “Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try again. Fail again. Fail better.” ◼

About the Author

Nick is in his second year as Associate Principal/Athletic Director at Columbia River HS in Vancouver Public Schools. He is the former Math, Spanish, and PE teacher and head track coach at Jesuit High School in Portland, OR.

Find us on

Association of Washington School Principals

Washington Principal | Volume 2 – 2020-21